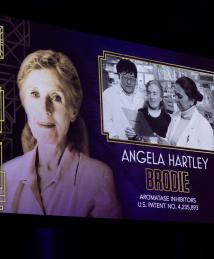

Angela Hartley Brodie

Angela Hartley Brodie discovered and developed a class of drugs called aromatase inhibitors, which are among the leading therapies against breast cancer.

Brodie was born in Oldham, Lancashire, England. She attended Ackworth School, a Quaker boarding school that emphasizes finding goodness in oneself and others. Brodie’s father was an organic chemist, and he supported her broad-ranging interest in science. In fact, he urged her to pursue a career in science at a time when women were not typically encouraged to enter such fields. “He was always talking to me about science,” Brodie said. “Always interesting me in it.”

She earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biochemistry from the University of Sheffield in 1956 and 1959, and her doctorate in chemical pathology from the University of Manchester in 1961.

In 1962, Brodie moved to the United States and joined the steroid biochemistry training program sponsored by the National Institutes of Health at the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology, a nonprofit biomedical research institute in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts. There, she met her future husband, Harry Brodie. Each researched the biochemistry of aromatase for different purposes. Harry Brodie was interested in its application to contraception, while Angela Brodie was determined to identify a link between estrogen biosynthesis and the needs of breast cancer patients.

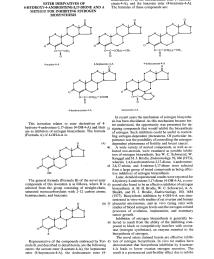

The Brodies spent the 1970s optimizing the first selective aromatase inhibitors, developing methods of administration and testing synthetic compounds to block estrogen synthesis. One compound, 4-hydroxyandrostenedione (4-OHA), proved to be particularly effective.

In 1979, Angela Brodie moved to the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore and began manufacturing clinical-grade material in her own laboratory. She was a professor of pharmacology at the School of Medicine and a researcher in the Hormone Responsive Cancers Program at the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center. Promising results from the first clinical trial in 1981 spurred further testing of 4-OHA. Subsequent studies showed that 4-OHA reduced blood estrogen levels.

In 1993, pharmaceutical company Ciba-Geigy brought 4-OHA, known as formestane, to market to treat advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women. It was the first new agent in a decade explicitly developed to treat breast cancer.

Many breast cancers are hormone dependent, requiring estrogen to reproduce and grow. Aromatase inhibitors work by interfering with aromatase, the enzyme that catalyzes the key step in the body’s synthesis of estrogens, thereby starving hormone-dependent cancers of their estrogen fuel supply.

Currently, three aromatase inhibitors are FDA-approved: anastrozole, letrozole and exemestane. Thanks to Brodie’s pioneering work and her belief that “women deserved better” in the treatment of breast cancer, it is estimated that 500,000 women worldwide now receive aromatase inhibitor therapy every year.

Named on 13 U.S. patents, Brodie was a Fellow of the American Academy for Cancer Research (AACR), and her many awards include the Dorothy P. Landon-AACR Prize for Translational Cancer Research and the Brinker Award for Scientific Distinction from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. In 2005, Brodie became the first woman to be honored with the Charles F. Kettering Prize from the General Motors Cancer Research Foundation.