Charles Richard Drew

One of the world’s most impactful surgeons, educators and innovators, Charles Drew invented a safe way to store, process and transport blood plasma. His work not only saved lives during World War II, but it also revolutionized blood plasma storage through the process of blood banking and continues to save lives today.

Drew was born in Washington, D.C., in 1904. His desire to pursue a degree in medicine was influenced by the experience of losing his sister to tuberculosis while he was in high school. Working toward this goal, in 1922 he earned a football and track and field scholarship to attend Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he was one of only 13 Black students in a student body of 600.

Drew received his bachelor’s degree in 1926, and to earn the money he needed to attend medical school, he worked for two years as a biology instructor and coach for Morgan College (now Morgan State University) in Baltimore. He then enrolled at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

At McGill, Drew immediately distinguished himself, winning the J. Francis Williams Prize in Medicine and the annual scholarship prize in neuroanatomy, working on the McGill Medical Journal and being elected to the medical honor society Alpha Omega Alpha. He completed his medical and master of surgery degrees in 1933.

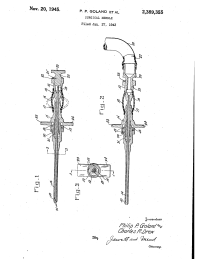

During his internship and residency at Royal Victoria Hospital and Montreal General Hospital, Drew studied issues related to blood transfusions, or the process of transferring blood through an intravenous line (IV). Continuing his research in this area, he earned a Rockefeller fellowship in 1938 and pursued a doctorate at Columbia University, where he began working with physician John Scudder. Together, Drew and Scudder conducted extensive research in blood preservation and fluid replacement, and developed a trial blood bank. Drew’s 1940 doctoral thesis, “Banked Blood: A Study in Blood Preservation,” cemented his status as an expert in this developing field.

Drew’s breakthroughs in blood preservation occurred at a critical time, as World War II was ongoing in Europe, and Great Britain needed large amounts of blood and plasma to treat its wounded soldiers. Using the experimental blood bank they had just tested as a blueprint, Drew and Scudder spearheaded the “Blood for Britain” program to ship plasma overseas.

The delivery of plasma was crucial. Blood contains two primary components, red blood cells that carry oxygen throughout the body, and plasma, which is primarily water mixed with proteins and electrolytes. Plasma is effective in helping replace essential fluids and treating shock, two functions essential to saving lives. Additionally, plasma on its own is easier to preserve and transport, and it can be used with any blood type. Drew and his team developed novel ways to extract, preserve and ship plasma on a large scale, sending 5,000 lifesaving liters of plasma to England.

Following the success of the “Blood for Britain” program, in 1941, Drew became both the first Black surgeon to serve as examiner on the American Board of Surgery and the first director of the American Red Cross Blood Bank in New York. He created several mobile blood donation stations, which would later be known as bloodmobiles.

Despite the great need for blood as the U.S. entered World War II, the armed forces insisted that the Red Cross pilot project follow a racist policy, excluding Black donors. Though in January 1942 the Red Cross announced it would begin accepting blood from Black donors, it would still segregate the blood. Of course, Drew objected to such policies. In 1944, he wrote a letter to the director of the federal Labor Standards Association regarding the segregation of blood by the National Blood Bank. Drew wrote, “It was a bad mistake for 3 reasons: (1) No official department of the Federal Government should willfully humiliate its citizens; (2) There is no scientific basis for the order; and (3) They need the blood.”

Following his work with the National Blood Bank, Drew focused his efforts on training and mentoring his surgical residents and medical students. In 1944, he was appointed chief of staff at Freedmen's Hospital, he was elected Fellow to the International College of Surgeons in 1946, and he served as a consultant to the surgeon general in 1949.

At the time of Drew’s death following a serious car accident in 1950, he was professor and chief of surgery at Howard Medical School. His legacy endures through his many contributions to health and education, and through those he continues to inspire, including his daughter Charlene Drew Jarvis, who has held positions as a neuroscientist, legislator and university president.