John R. Adler Jr.

"A lot of people who achieve things in life will tell you - it's not about brains. It's much more about persistence."

Neurosurgeon John Adler invented the CyberKnife stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) system, which enabled precision robotic, image-guided therapeutic radiation without skeletal fixation. Today, the CyberKnife is used around the world to noninvasively ablate tumors and other abnormal lesions anywhere in a patient’s body.

Born in 1954, Adler grew up in the small rural town of Hazardville, Connecticut. As a boy, his life was consumed playing Little League baseball, roaming the ever-present woods and actively participating in Boy Scouts, where he achieved the rank of Eagle Scout. Paid work was a regular part of his life from his first paper route at age 11. In an interview with the National Inventors Hall of Fame®, Adler said his character was indelibly shaped by two principles taught to him as a young boy: “It is ‘sinful’ to waste your God-given talents,” and “Always leave your campground better than you initially found it.”

Adler’s passion for science began in high school. “I got a glimpse into what science was, especially chemistry and the biological sciences, and that struck me as incredibly cool,” he said. “I always was innately, from there on, science oriented.” He studied biochemistry at Harvard College, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1976, followed by his medical doctorate from Harvard University in 1980.

Adler’s 1980-87 Harvard neurosurgery residency was interrupted for one year (1985-86) so he might do a fellowship at the Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden, largely under the tutelage of legendary neurosurgeon Lars Leksell. Adler was “blown away” with Leksell’s radiosurgical concept of noninvasive brain surgery as embodied by his GammaKnife system, but he also recognized that this technology could only be used for tumors in the head. Moreover, to accurately target and treat patients in the GammaKnife, patient’s skulls needed to be somewhat invasively and painfully clamped into the machine so they could not make even slight movements. “Leksell introduced to me a timeless principle – that we, especially in the brain, should think about making surgery noninvasive,” Adler said. “So it was logical to say if this can work well in the brain, maybe the principle and benefits of noninvasive surgery might be universal, and if so, why not everywhere in the body?”

In 1987, Adler moved to Stanford University, where he began his march up the ranks of the university professoriate in the departments of neurosurgery and radiation oncology. Here, in collaboration with faculty colleagues and Silicon Valley experts in computer science, robotics, and both imaging and radiation physics, he designed a complex mechanical system that would later be termed the CyberKnife, a technology that could accurately administer high-energy X-rays to a target inside the human body while dynamically adjusting the position of these beams using real-time 3D imaging.

To treat inoperable or surgically complex tumors, the CyberKnife system uses a compact, robot-mounted LINAC, or linear accelerator, which precisely moves around the patient to deliver X-rays from widely dispersed angles. Using Adler’s principle of “image guidance,” this “surgical” device tracks a patient's exact 3D spatial coordinates in real time, always keeping a narrow (yet variable) beam of radiation focused on the tumor, regardless of voluntary or involuntary (breathing) movements. This allows clinicians to deliver significantly larger doses of radiation to tumors without damaging the surrounding healthy tissue. The unique real-time image analysis provided by the CyberKnife eliminates the need for rigid head frames, or cumbersome and inaccurate stabilizing body casts.

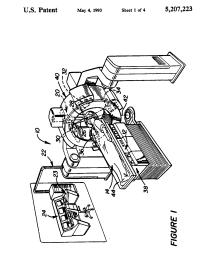

Though Adler chronically struggled to secure funding for his invention, he ultimately succeeded in making the CyberKnife and image-guided radiation a reality. “A lot of people who achieve things in life will tell you – it's not about brains. It's much more about persistence,” he said. He filed for a patent in 1990, and it was granted in 1993. In 1994, he used CyberKnife to perform the first robotic, image-guided radiosurgery treatment at Stanford. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared CyberKnife for treating lesions in the brain and base of the skull in 1999, and for treating tumors anywhere in the body in 2001.

With CyberKnife, Adler changed the trajectory of all therapeutic radiation, thereby enabling dramatically new applications for radiosurgery to be created. Today, image-guided techniques are commonplace throughout the radiation industry. CyberKnife is widely used for the treatment of primary and metastatic tumors in the brain, on or near the spine, and in the breast, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas and prostate. Adler stated that by 2018 more than 1 million patients had been treated by CyberKnife globally, and multiples more have been treated by subsequent derivative technologies.

In 2009 Adler co-founded Cureus, a free, open-access, multidisciplinary medical journal with a mission to provide universal access to medical research articles. Over the years, it has become one of the largest journals in medicine and is still growing fast. In 2014, he founded Zap Surgical Systems Inc. to make radiosurgery more accessible to patients around the world. In 2017, another of Adler’s inventions, the ZAP-X® gyroscopic radiosurgery robot, received FDA clearance to treat tumors, lesions and other conditions in the brain, head and neck. The first and only vault-free therapeutic radiation instrument, ZAP-X eliminates the need for costly shielded radiation treatment vaults, while also delivering even higher quality, more precise radiosurgery. Adler hopes this technology will allow community hospitals and rural outpatient centers worldwide to afford and deliver the highest quality radiation, thereby replacing more conventional surgery.

Adler’s honors include the American Association of Neurological Surgeons Cushing Award for Technical Excellence and Innovation in Neurosurgery in 2018 and the American Radium Society Janeway Medal for Lifetime Achievement in 2022. Reflecting on his work, Adler said, “Most people think my accomplishments are greater than life-size, but to me they're simply the product of putting one brick on top of another brick, on top of another brick, and not stopping even when things get very tough.”