Emil J Freireich

Oncologist Emil J Freireich and engineer George Judson developed the first continuous-flow blood cell separator. Machines based on their invention have been vital for improving outcomes for leukemia patients and developing new approaches to treating cancer and other diseases.

Born in 1927, Freireich was the son of Hungarian immigrants, and he grew up in Chicago during the Great Depression. “My mother worked in a sweatshop. My father died when I was 2,” Freireich said. He developed an interest in physics, and his high school physics teacher advised him to attend college.

Freireich earned his bachelor’s degree at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and his medical degree from the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Chicago. Over the course of his career in oncology, he came to be recognized as “a founding father of modern clinical cancer research.” Following a fellowship in hematology at Massachusetts Memorial Hospital, in 1955, he moved to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. Here, he served as a senior investigator and led the leukemia program. “Leukemia at that time was a horrible illness – a death sentence,” Freireich said. “Most children lived only eight weeks after being diagnosed. Ninety-nine percent died within a year.”

A cancer characterized by an excess of abnormal white blood cells, leukemia can prevent blood from clotting. Though early chemotherapy drugs were available at the time, patients often died of blood loss before they could undergo treatment. Freireich believed leukemia patients’ bleeding was caused by insufficient platelets, which help the body form clots, and he proved this when he mixed platelets from his own blood with blood from leukemia patients, stopping the bleeding. He had discovered a lifesaving treatment procedure for leukemic children: transfusion of platelets from freshly donated blood to prevent excessive bleeding. To make this procedure feasible, he needed an efficient method to isolate large amounts of platelets from donor blood. He would find his solution in collaboration with Judson.

In 1962, Judson, an engineer working for IBM, brought to Freireich his idea for the continuous-flow blood cell separator. Judson’s son Tom had been diagnosed with leukemia, and the engineer envisioned a way to improve the process of removing diseased white cells from a patient’s bloodstream, a method for treating leukemia. Freireich sketched some broad requirements for a device and within months, the co-inventors began developing a prototype.

Having been given a yearlong paid sabbatical from IBM, Judson joined Freireich in his lab at NIH in June 1962. By 1963 they had produced a working prototype. Judson then led a group of engineers at the IBM Development Laboratory in Endicott, New York, to complete the project.

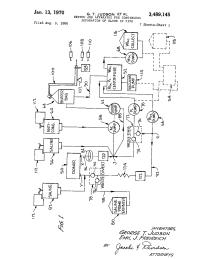

The NCI-IBM Experimental Blood Cell Separator (which evolved to become the IBM 2990 and IBM 2997 models) was introduced in October 1965. By this time, Freireich had moved to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, where he began testing the device. A revolutionary advancement in blood processing, this invention provided practical, lifesaving treatments for leukemia patients. It contained a centrifuge that would spin the blood donor or patient’s blood, and pumps that would move the blood through a separation channel and dispense the isolated components. The machine returned the rest of the blood to the donor or patient, all in a continuous flow.

Today, blood cell separators are used by blood banks, hospitals and laboratories worldwide. In addition to treating leukemia, they also are used to treat sickle cell disease, acute Guillain-Barré syndrome and symptoms associated with cancer treatments, as well as to collect peripheral blood stem cells for bone marrow transplants and for the collection of lymphocytes used for CAR T-cell cancer immunotherapy.

In addition to developing the blood cell separator, Freireich and his NCI colleagues also introduced combination chemotherapy, in which cancer drugs are given simultaneously rather than singly. Speaking about the first children to be treated with combination chemotherapy, Freireich said that 90% of them went into remission immediately. “It was magical,” he recalled. Currently, the five-year survival rate for children with acute lymphocytic leukemia, the most common childhood leukemia, is about 90% overall, according to the American Cancer Society. This is considered Freireich’s most important contribution to oncology.

After 50 years at MD Anderson, Freireich retired in 2015, though he remained a part-time faculty member in the Department of Leukemia until he passed away in 2021. His many honors include the Leukemia Society of America Award for Outstanding Service to Mankind in 1980, the Charles F. Kettering Prize in 1983, the MD Anderson Cancer Center Lifetime Distinction in Mentoring Award in 2015, the American Association for Cancer Research Award for Lifetime Achievement in Cancer Research in 2019 and the American Society of Clinical Oncology Distinguished Achievement Award in 2021. “Humans cannot live without hope,” Freireich said. “Hopelessness is the greatest trauma a person has to suffer.”